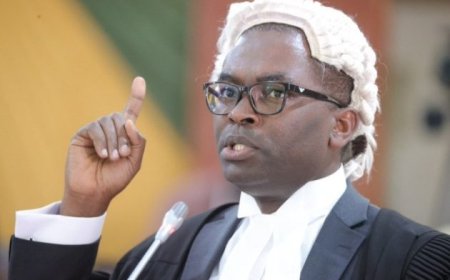

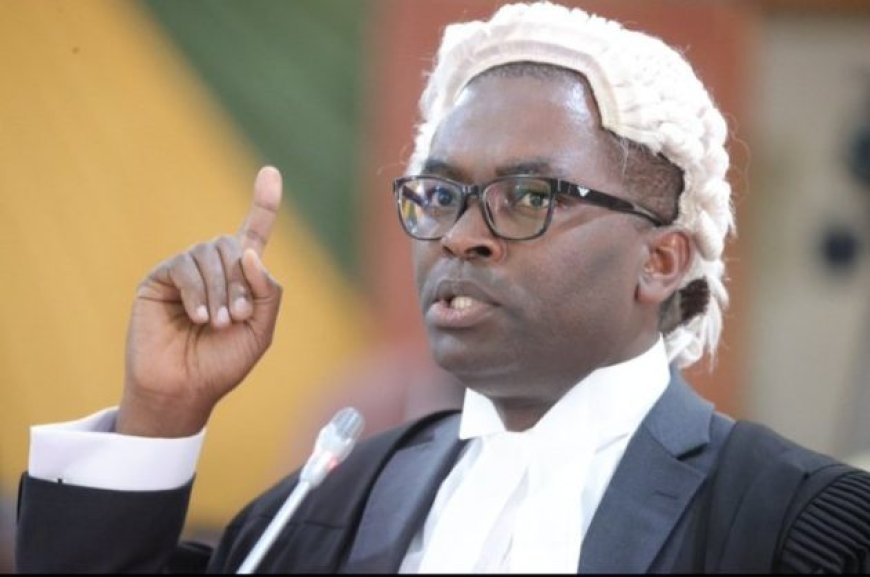

Advocate Dr Muthomi Thiankolu: The law may float through the cloud, but it lands on real bodies with real consequences

There are concerns about allowing every nascent and backwater University to offer the law degree program; at least there are five fundamental structural issues regarding legal training and education in Kenya.

The first fundamental structural issue revolves around the Kenya School of Law (KSL) and its de facto monopoly (previously, de jure monopoly) in offering the Advocates Training Program (ATP).

In or around 2004, elitist lawyers complained that the introduction of parallel degree programs in local universities was churning out too many “half-baked” law graduates.

These complaints led to the termination of exemptions that local graduates previously enjoyed from: (i) attending classes at KSL; and (ii) sitting examinations at KSL.

My generation protested the termination of exemptions vigorously. We argued that requiring us to attend KSL to learn, under the same tutors and courses we had already studied and been examined on at the university, was illogical and punitive.

We also asked an important question that remains unanswered to date: What “magic” does the Kenya School of Law possess that presumptively guarantees quality legal education, which all local and foreign universities are deemed incapable of achieving? Especially considering that KSL’s facilities and lecturer-to-student ratio are comparable to those of a single university?

Twenty years later, no study has been conducted to determine whether KSL’s infrastructure and staffing are compatible with its de facto monopoly over ATP.

Every year, we hear that the pass rate at KSL hovers around 20 percent. How can the pass rate be different when a single institution accepts graduates from numerous universities but operates with resources comparable to those of a single university?

The other fundamental structural flaws about legal education and training in Kenya, which are even more serious than the one outlined above, revolve around four interrelated issues.

We have an outdated but legally entrenched core legal education and training curriculum, which was initially meant to serve the needs of a small and elitist British settler community.

A colonial but ‘pretentiously plural’ legal system that relegates culture, traditions and institutions to the margins of formal law. This results in the problem of unemployment for law graduates and concerns about a “flooded market” when the structural issue is a limited market for legal services, attributable to the fact that most citizens arrange and conduct most of their personal and business affairs outside of formal legal channels.

Misguided obsession with training lawyers for the Kenyan domestic market. To illustrate, we hardly train lawyers who can competently compete for opportunities in international organisations such as the WTO panels, the WTO Appellate Body, the ICSID, the International Criminal Court, the United Nations Internal Tribunals, the International Court of Justice, the European Court of

Human Rights, the East African Court of Justice, the COMESA Court, etc. We are content to emphasise a curriculum that only prepares Kenyan lawyers to practice the “sixteen subjects” when the international market for legal services is much bigger than Kenya’s domestic market for such services.

Thoughtless obsession with virtual courts and virtual education. Although many will validly argue that online courts and online education represent a significant improvement over the pre-COVID-19 era, we have, in our typical African fashion, been unimaginative and inflexible in our harnessing of technology.

As a result, we now have a generation of lawyers who have never interacted with a real professor in a real classroom, never argued a case before a real judge in a real courtroom, and never cross-examined a witness in real life. In other words, courts became Zoom rooms, lectures became pixelated monologues and advocacy became what happens between muted microphones.

Although the emerging generation of Kenyan lawyers received their legal training online and practices the law online, the law is real, affects real people and operates in the real world rather than the virtual world. The law may float through the cloud, but it lands on real bodies with real consequences.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0